Strad Magazine jan. 2011

However, I felt my training was devoid of real knowledge of the nature of tone.

Some of us at school began doing work on plate tuning. This happened mostly outside the school walls and satisfied some of the curiosity.

Fairly soon, I became less convinced that free plate tuning was relevant to the dynamics of the completed instrument, but in the spirit of agnosticism carried on recording weights and frequencies.

I devoured a plethora of stringed instrument recordings and attended as many concerts as my budget would allow, with the conviction that listening actively, was and still is the key to understanding tone. There was however the perplexing need to associate that tone with some physical aspect of the instrument, other than simply "working in the correct way".

After having worked several years solely making instruments, I began studying the vibrations of my finished instruments. I hijacked some of the tools of plate tuners and started suspending finished instruments over a loudspeaker hooked up to a signal generator. With ear protection I would sweep a sine wave through the body of the instrument, while lightly touching the surface with my fingers. This was a kind of rudimentary analogue modal analysis, at a time when only the scientists did this sort of work. I had seen the diagrams of Marshall in the Catgut journals, so I could envisage basic modal shapes as I felt their presence. I also strewed sawdust onto the surface and in through the f-holes to see nodal lines. I did some demonstrations of this method at the Newark school several years later and showed it to colleagues, and was rather surprised to find that most people felt sorry for me, and that I had veered off the "path".

The limitations of this method are that above around 1000hz there are no readily recognisable modes, as they become a conglomerate of increasingly small and complex movements, also you need some fairly loud sounds to excite the instrument, but the largest contributors to radiated sound are the signature modes and there is only a small number of them.

Today I use modal analysis, with impulse hammer, accelerometers and microphones, to map my own instrument's behaviour and also measure fine instruments that come my way. I am a participant of the Oberlin acoustics workshop and am glad to engage with some peers that I admire there. My local medical clinic has also been very supportive of my CT scanning instruments of calibre.

Of course I also use the very sophisticated technique of biting my wood and throwing it on the floor for the finer assessments.

One thing is certain, and that is that what I have learned through the application of technology has made my instruments sound much better. No doubt.

Is technology always a good thing, or is new technology having a detrimental effect on violin making?

My making is traditional. The tradition is characterised by the thirst for knowledge. Knowledge cannot be detrimental.

Where do you think advances in technology will take violin making? Will it enable luthiers to build the perfect instrument?

Primarily the new knowledge will change the way makers envisage the workings of their instruments. This will lead to potentially beneficial changes. With the most sophisticated scientific methods and machinery , one will however still be able to make an absolutely awful instrument with considerable ease. Intuitive work is an open system, which fumbles a bit in the dark. Science is closed, it affirms or negates. Both are exciting and possibly mutually beneficial, but violin making will not be interesting if it becomes a pure science. Technological advancement in violin making is definitely a speed inhibitor and does not increase production. On the contrary it forces you to put more thought and work into the making.

How has the internet – including websites, email, forums and Skype – helped your making?

Makers are finally engaging in a sharing of knowledge and a tactical discourse in the spirit of openness spurred by the internet.

The net has transformed the world and hasn't excluded the violin makers. Secrets are "passé".

Reykjavik Grapevine August 2010

World-renowned violinmaker, Hans Jóhannsson, talks about making stringed instruments in the 21st century

20.8.2010

Words by Emily Burton

Photos by Julia Staples

“When I listen to music, I very often don’t listen to the music; I just listen to the instruments. Otherwise, I get involved with an emotional situation, which is what we are all after; but in order to learn about the nature of the sound, I have to kind of forget the music.”

Stepping into Hans Jóhannsson’s violin workshop feels like stepping into an 18th century science lab. A beaker filled with amber-coloured varnish bubbles and hisses in the corner. Jars of oils, a scale, syringes, mixing bowls and test tubes line the windowsills. Parts of instruments hang from the walls. Hans shows me his latest creation, a classical violin made from his own model. Inside the label reads ‘Berlin-Reykjavík’, the two cities he divides his time making violins and other stringed instruments.

Hans has been making violins for 33 years. He studied the craft in England for 3 years before moving to Luxembourg, where he worked at the Chateau de Bourglinster, an isolated, 12th century castle. Inspired by the seclusion and fairytale-like environment, Hans concentrated on making violins for twelve years. Today, he continues to only create, shying away from the business side of making violins, restorations, and repairs.

Hans spends a little over two months designing, making varnish, and sculpting the wood for a single instrument. Unlike most violinmakers, he does not make copies of instruments. Hans works from his own classical model and makes small changes every year. He describes the experience as a lifelong process. He also makes strange instruments. I sat down with Hans to ask him how he got his start creating stringed instruments, and what the future holds for violin making.

How did you get started in the violin making business?

My grandfather was a cabinetmaker. I used to hang out in his workshop when I was a kid, and I suppose my interest in working with wood comes from him. There weren’t any musicians in my family. In my teens, I played jazz violin and guitar, but I never had any formal training in classical music. I think I was about twelve or thirteen when I decided that violin making was what I really wanted to do.

What is special about the way you make violins?

I am now heavily into the science of violin making. I do a lot of computer analysis of tones and sounds. I am involved in a group that is a part of the Catgut Acoustical Society in the US. Every year we meet in Oberlin at the music conservatory. It’s a diffusion of what people have learned in past decades and the sciences of modal analysis of instruments. It’s the same knowledge that is used to design airplanes and cars and anything you can think of that moves and is dynamic.

There are few good, classically trained makers in the world who have made the effort to learn a little bit about objective analysis. It’s all about finding out how the instrument moves at different frequencies, because that teaches you specifics about the density of the wood and where to remove wood to make it work in a certain way. It’s an interesting way to learn how to control the sound of an instrument, for example, how to make a bright or a dark sounding instrument.

Can you explain the science that you use?

I put a little motion sensor, called an accelerometer, on the bridge of the instrument. Then, I go around the whole instrument with a tiny hammer with a motion sensor in it as well. I collect all the data from each point on the instrument as it starts to move. The software takes all of the information and makes a map of the whole instrument. The software was developed by an ingenious violinmaker in England named George Stoppani. You can make little animations of how the thing is moving. The animations show me things that I couldn’t possibly realise on my own. It’s a revolution in the way we think about sound.

How has that changed the way you make instruments?

The work doesn’t become completely scientific, because violin making is based on tacit knowledge. It changes the picture that I have in my head of what it is that’s making the sound and how the instrument is behaving. I don’t see the reason for the dichotomy between traditional, empirical ways of doing things and the scientific way. I think it is a mistake to separate things out and refuse to think about objective analysis in violin making.

When scientists are at their peak, it usually has to do with their frame of mind. Traditionally, people don’t think about a scientist as being a creative person, but that’s exactly what it’s all about. There are a lot of violinmakers that are really sceptical about science, because they think that if you objectify things that are done with intuition, then you somehow destroy them. I don’t agree with that.

Tell me about the strange instrument you make.

I love the baroque form of the classical violin, but the whole aesthetics of the violin belong to the baroque era. It’s intriguing that something so great has remained unchanged for almost 400 years; whereas, everything else is developing—chairs, tables, cars and things are constantly evolving. I always wanted to try and create something that had to do with our times. I’ve been working for a few years now with an architect in Oslo, Andreas Eggertsen, and an artist in Berlin, Ólafur Elíasson. I needed to work with other people, because otherwise I would always be stuck in my way of thinking. The classical music scene is kind of conservative and not willing to accept big changes. My line of thinking was that if I were collaborating with an architect and artist, their whole approach would be completely open. There is an incredible amount of experimentation and a lot of interesting, contemporary thought in those spheres.

We decided to do some preliminary tests and experiments. First of all, we wanted to make a stringed instrument that anybody who had learned to play the violin, viola, cello or double bass could pick up and feel at home with. We didn’t want to create a new culture. We could’ve made a wacky instrument, but then we would’ve had to make a whole new culture around it. We started thinking about the phenomena of resonance and how that fits in with shapes. The Germans have a really good word called “gestalt.” It’s more than shape; it’s how a shape functions as more than a sum of its parts.

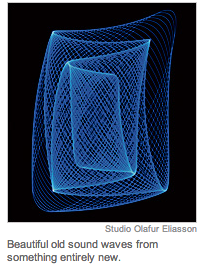

Ólafur had been doing some studies on three dimensional vibratory designs that he made a few years ago based on a harmonograph. It had three swinging pendulums, which if you tuned them to a harmonic series, you would get these beautiful shapes drawn in three dimensions. We thought we would try, just for fun, to make a shape that would be an efficient resonator to amplify the string sounds. Using that as a basis, we also did a lot of studies on animal shapes, plant shapes and organic, natural shapes. Insects have outside skeletons or shells that can withstand tremendous forces and distribute vibrations really well. There was a resonator that worked quite well that was based on the shape of a beetle. Then, we fused those two kinds of things together and we made a series of resonators out of wood, which I carved. They were wooden resonating sculptures.

How did the sculptures work?

I made a series of sculptures, each one resonating in its own frequency range. We did this sound installation in London where we placed the resonators in different parts of a building designed by Ólafur. The acoustics were strange, which suited us well. We got this incredibly good English violinist, Thomas Gould, to improvise. We channelled the signal from his electric violin to these electromagnetic drivers (like a speaker without a paper cone). The violin was one I made out of wood, but it was just like a skeleton violin—it had no resonating body of its own.

The next stage was to make a real instrument, a real violin. A couple of years ago I carved a violin out of wood that was based on these harmonic shapes. Last October we had a concert in the library in Alexandria, Egypt. We got this really good Egyptian violinist, Khalid Owaieda, to improvise some Arabic Sufi tunes. It’s a violin, but it’s based on modes of thinking that belong to our time. It actually kind of works. It still needs some development, of course. For me fooling around with this new instrument is even more exciting, because people haven’t done very much, not in this way.

So what’s next?

The next project is to make a two-way violin. It’s going to be like a two-way speaker enclosure with two or maybe three chambers. Each chamber will take care of its own frequency range. You can play modern music on a classical violin, and you will be able to play early music on the 21st century violin. Music transcends the form and the “gestalt” of an instrument.

Do you think a really great violinist can transcend an instrument?

A good player can make a cigar box with rubber bands sound good. Do you know the story about Jascha Heifetz? After a concert some lady told him, “Mr. Heifetz, your violin sounds wonderful.” He put his ear up to it and said, “That’s funny, I don’t hear a thing.” The sound that you hear has a lot to do with the person playing. In fact, when we are trying to do acoustic listening tests, one thing that is really difficult is, if a player is really good, he or she will give so much of the tone from the way the fingers are pressed onto the fingerboard. It’s hard to be completely objective, because you can’t take that away.

Why are older violins so popular? Is it true that violins get better with age?

When you assemble an instrument, the wooden parts have to support quite a lot of tension. In the first few months and maybe even the first three or four years, all those different parts are getting used to being subjected to that pressure all the time. Also, things like fingerboards and necks can get used to a certain player and vice versa. The player and the instrument are like a symbiosis—they are like two ends of the same thing. The monetary value of an instrument has a psychological effect. No one believes that an instrument worth 2 million dollars is not laced with a certain degree of quality. On the other hand, the fact that the world's best musicians have been the only people using the old valuable instruments has helped to enhance their reputation.

Myth or no myth, some of the old masterpieces are truly awe-inspiring. There were just some incredibly talented people around at the time. There was an amalgamation or mingling of all kinds of different interests and disciplines. If you were making instruments, you were probably fooling around with astronomy or maths. I think the same thing is happening today. I think violin making is becoming great again.

New York Times April 2010

Strad Magazine March 2010

International Herald Tribune (later Times)

The unorthodox components are the early fruits of a research project initiated by a classical violin maker (Hans Johannsson), an artist (Olafur Eliasson) and an architect (Andreas Eggertsen). Their objective is to reinterpret the traditions of 17th- and 18th-century violin making using today’s technology and a contemporary visual aesthetic.

Other musical instruments have evolved over the centuries, as have musical taste and our ability to detect different sounds. But the stringed instruments invented in the 1600s and 1700s by great Italian masters like the Stradivaris and the Guarneris are still imitated by modern instrument makers. “Classical instruments are revered by players and makers alike, but that shouldn’t prevent us from breaking new ground,” Johannsson says. He says he also hopes to correct some of the shortcomings of traditional instruments — like so-called wolf notes and restrictions on tonal control — as well as to experiment with the sonic properties of synthetic materials.

Johannsson and Eliasson began work on the development of the new instrument after a conversation in the summer of 2005. Eggertsen then joined the project, bringing with him the digital algorithms he uses to create three-dimensional shapes in his architectural work. The next stage of development will be to combine the five resonators into a single unit as part of a mechanical instrument rather than an electrical one. Once it is finished, the new instrument will play the classics, although its designers say they hope it will inspire composers to write new music too.

From NY. Times dec.9,2009

Alice Rawsthorn